In the decade of the 1990's the visibility of Cuban women writers on the island began to change. This happened at the same time that the country plunged into the Special Period. When the Soviet Bloc disintegrated in the early 1990s, the concept of “future” mobilizing public policy and speech was compelled to take a turn. A new space of humanity—and inhumanity too—surpassed the grand narrative of the epic man, and gazed into the quotidian themes and everyday shortages. Although the emotional regime maintained a considerable uniformity, the initial destabilization of State control over some spaces of social interaction left room for more varied emotional repertories.

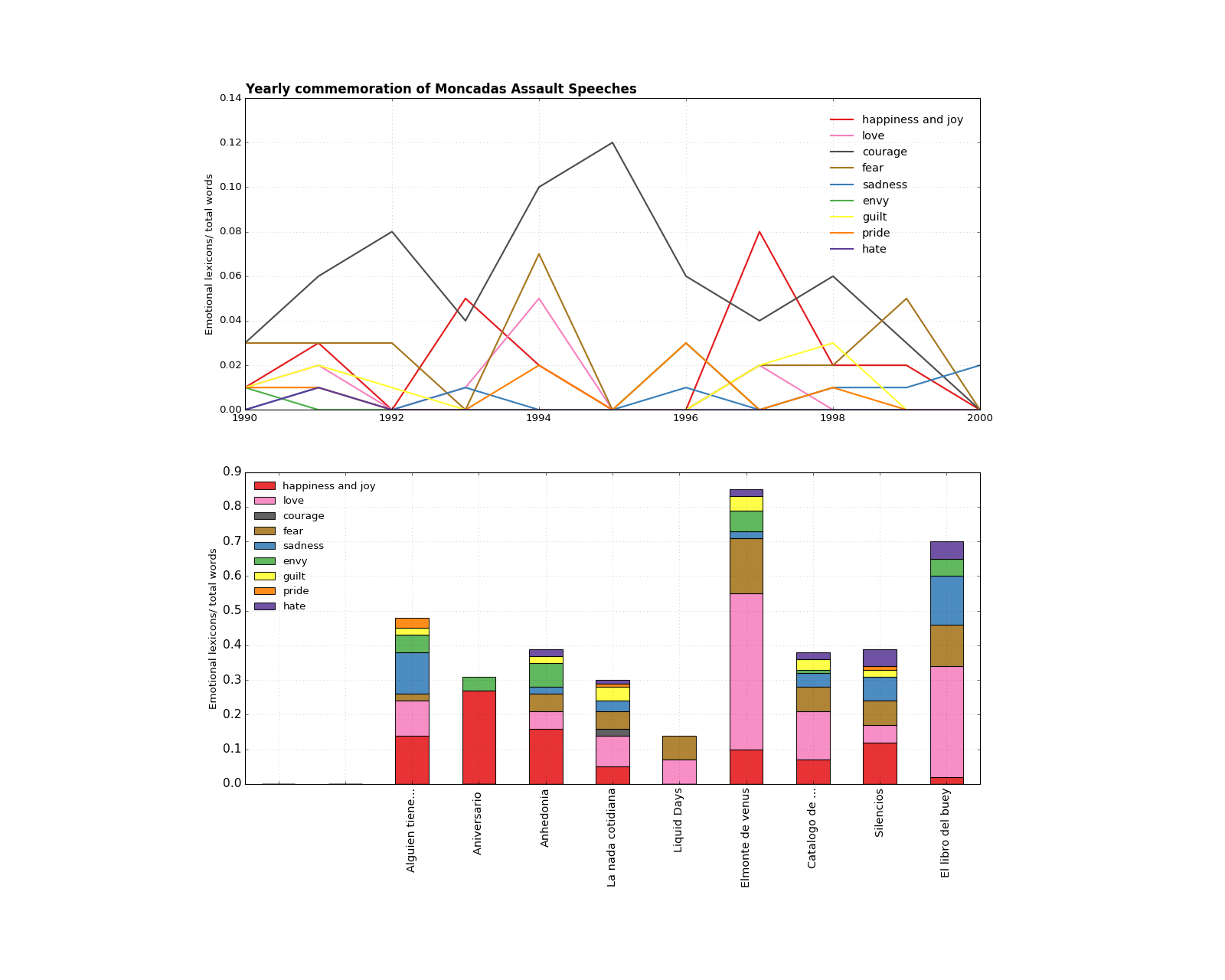

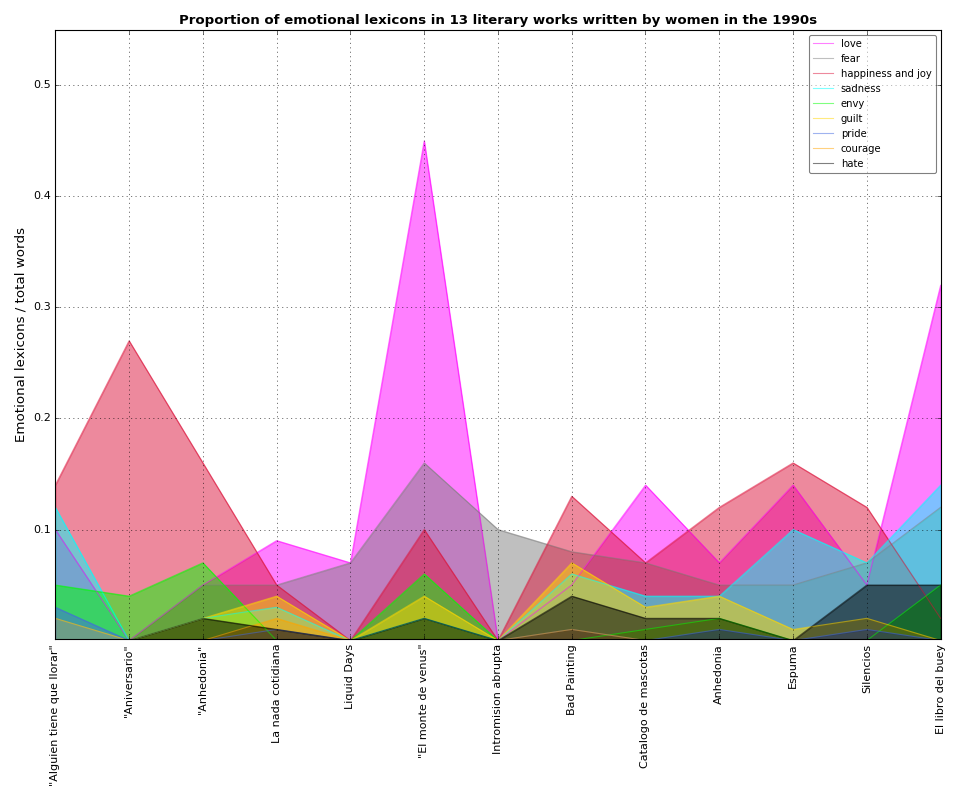

Looking at its "emotional coverage" —once we did the difference of means test—literature written by women, at least the sample here studied, is more emotional than Fidel Castro speeches (see below), but the next step would be to see in which way. Yet, they seem to be in the same range. Literary works in this graph share a similar range of emotional coverage, except for two outliers that surpass the 0.6 % emotional coverage.

The list of literary works plotted is:

"Alguien tiene que llorar"

"Aniversario"

"Anhedonia"

La nada cotidiana

Liquid Days

"El monte de Venus"

"Intromision abrupta de esos dos personajes"

Bad Painting

Catalogo de mascotas

Anhedonia

Espuma

Silencios

El libro del buey

If you know them. Do you want to take a guess, and point which fuchsia dot is which book? Hover on this graph to find out the answers.

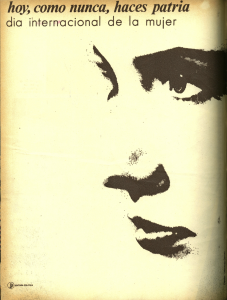

The reason I am comparing literature written by women with the official discourses is that the autonomy of women was placed "within the revolution". Here is a fragment of an interview done to one of the women who first called attention to the scarce presence of women in the literary field:

This thing about the “Revolution within the Revolution” is fine, but it is a social Revolution in which women go after.

The woman was last in queue for rights, of course. In this work there is a paragraph that upsets because it says the Federation of Cuban Women is a chain of transmission between the government and women. What in other countries is seen as 'women fought , women conquered' , here it is seen as 'the woman received , the woman was given' and that always marks. Here women's successes are the results of the work of colleagues who have sacrificed so women can etc., etc. (Arenas cálidas, 102, my translation)

If emotional repertories are to be understood, they need to be placed in the context of the set of norms that predominate in the emotional regime. Especially, because the battles conquered by the female subject were always placed inside the battles of the Revolution. Nothing outside of it.

"Aniversario"

The point of entry for this combination of emotional evaluations in history and in literature is for me this short story called “Aniversario”. The short story’s time and place coincides with the commemoration of the Moncada’s assault on July 26, 1993. That day, Fidel Castro announced the legalization of the dollar, and “Aniversario” accounts for the generalized sense of inequity that began to grow. Coinciding in time and place with the historical event, “Aniversario” frames an emotional strategy that contests the official emotional regime. The short story is a monologue/phone conversation in which a woman in a hotel room tells the other one, apparently a friend, her experience of the 40th anniversary of the Moncada Assault, hence the name “Aniversario”. The short story uses the official repertoire that often privileges “happiness”, but subverts the conceptual parameters that support it. In this case, it isn’t the idea that happiness cannot be bought that the story conveys, but rather, that purchasing power permits misinterpretations, “malas lecturas”. This story offers an opportunity to contrast the 40th anniversary discourse –the time of the story—with the discourse present in the story itself. That would allow us to access the emotional regime lexicons together with the lexicons present in the narrative text. In both texts the emotional lexicons that predominate are happiness and joy. “Aniversario”, however, constructs through this emotion a distance between the subject and the reality. This is the punctum of the story, physical and affective distance.