Happiness

= is the goal of the Revolution

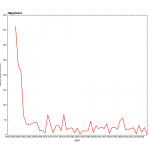

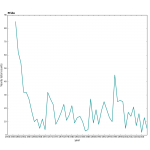

The Revolution is presented as that which makes the people happy. Happiness was at the beginning a bargaining element in getting more people from “the people” behind the Revolution. The first opposition developed appealing to happiness is one in which peace is not imposed by force but by the people’s collaboration based on people’s happiness. That is, peace through happiness is the first dispositive of the Revolution. This dispositive is built on the premises that “since the triumph of the Revolution, sadness became joy and pain became hope” (080559). As early as May 1959, Fidel Castro introduces a distinction between two types of happiness. One that derives from having a burden removed and another one that flourishes out of hope. One is the short-term; the other one is the long-term one. There is happiness for what was constructed, or to be constructed, and there is happiness for the destruction of privileges and abuses of the past. Happiness functions initially as barometer of the Revolution’s popularity. The revolution bring progress, and progress makes the people happy.

Few years later, the enemy, the imperialistic USA, will be clearly defined as the negative space of this subject of happiness: being sad for the things that construct happiness and happy when privileges and abuses are salvaged. The enemy wishes what is to be destroyed and seeks to destroy what is to be constructed. Later, the empire will be defined as unhappy for the progress that the Revolution brought.

Happiness is a right mentioned often in conjunction with the right to progress—education, housing. When it is mentioned as a right, courage and struggle are added to the framework that holds it. The people from then on cannot be afraid of fighting for happiness and has to be grateful (especially the young) for all those who lost their lives fighting for the happiness of future generations.

In terms of short-term happiness the people starts to be happy when it feels free. As for long term happiness, the people starts to feel happy when they struggle (lucha) for something.

Temporal tenses for emotions are set:

Yesterday= sadness and despair,

Today= happiness,

Tomorrow= hope.

When appealing to international imagery, Cubans are in the world to conquer not only their own happiness but that of all Latin America’s. At the time of massive expropriations, when happiness is mentioned, no unhappy bourgeoisie appear in this rhetoric platform, farmers, on the other hand, get their piece of land and with that, humiliation and despair disappear giving place to happiness.

Happiness characterizes the Cuban people. From 1961 on it is portrayed as a national trend. The “gusanos” (vermins), on the contrary, are defined as those who have relinquished this emotion, those who have renounced happiness (081161) Their type of happiness, as the one allocated to USA, is one sparked by vanity, privileges and egoism.

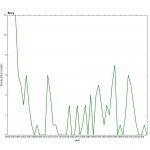

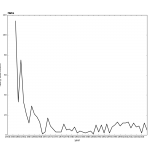

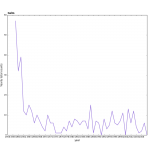

It is a constant to mention people that died and fought for the liberty and happiness of the present. By 1962, happiness is treated as a right already conquered that now has to be defended. Workers, another group dear to the Revolution, bring their labor, energy and intelligence spreading progress to bring happiness to the most remote areas. From 1967 to 1970 “work” (trabajo) is one of the most mentioned words in Fidel Castro Speeches when talking about happiness. (See wordcloud) Workers are expected to work more happily and enthusiastically because they are not subjugated by the chains of money. Work would bring dignity rather than humiliation.

Kids are often told how people died for them to be happy and also that their work—shows, debates, dances, etc.—bring joy to the people and to the higher ranks. A cultured, happy and healthy childhood are motive of international pride and the spectacle of it positively impresses foreign visitors. Happiness, and not only a good educational system, is part of the human capital that gives Cuba a good image. Youth, and any youth congregated in any official gathering brings happiness to the higher ranks and “would” bring happiness to the heroes—often a specific name like Camilo or Che is invoked—that gave their life for the Revolution.

1977 = happiness is a universal language

In 1977, for first time, envy for the happiness of youth is hinted at; later in 1996 this connection will be made explicit and will define largely the use of positive envy. (See envy) Around the 1970s work stops being homologated with happiness, becoming the other part of life together with sacrifice. Education and happiness are also separated. If in the beginning they were indissoluble: education would bring happiness and work makes people happy, later they were part of the rights and obligations of a citizen. In the future there will be happiness but also work and sacrifice.

In the 80s, when talking about the youth, happiness is often paired up with a sense of security. Having achieved the goal of happiness and education, revolutionary ideas and feelings are being harvested out of the technologies for an egalitarian society: “The secret of joy is to go deep into the revolutionary ideas and feelings” (050487)

Happiness is one of the things that do not abound in the capitalist societies because only the technologies of social egalitarianism characteristic of socialism can make the people happy. The Cuban people are reminded relentlessly that they are happy, and they have a privilege that most of the world does not have, to be happy. In a particular case, when trying to promote volunteer work in 1987, Fidel prizes the unpretentiousness of a surgeon who is doing manual labor, and finds him happy of taking a break from a work he did all his life, and proud to be working with somebody from the working class, able to perform physical labor creating with his hands instead of ‘only’ with his intelligence. When trying to push forward volunteer work, work and happiness are packed together again, but it is usually a question what brings them together not a maxim. For example: “Tell me, if we are going to be happy or not while working”; “we could ask the old lady of 76 if she feels more or less happy after her 600 hours of volunteer work, more or less healthy doing that” (291187). A good revolutionary must not be afraid of the rigors of hard work, and concurrently, ought to be happy with the fruits of labor and with the task achieved (el deber cumplido). An ambient of blameworthiness for those not working is later proposed.

There is very telling clarification in 1987, Fidel Castro states that he perceives a generalized emotional state that he calls “well founded happiness” (alegria fundada) and remarks that he is not confusing slogans and greetings for it. A certain spectacle of happiness seems to be acknowledged.

In the 90s, we observe a pattern of “first, but then” that could be said to be “pedagogic”:

Opposition1= USA is happy to invade Grenada and Panama but then its soldiers’ cadavers are repatriated and happiness is interrupted.

Opposition2= Occidental Europe was happy for the fall of the Berlin Wall but now is terrified because of the crisis and have no reason to feel happy. [Note: one of the slogans shouted in 1991 was “we are happy here”.]

Opposition3= Russian people were first happy about the capitalist measures introduced, later depressed by the economic debacle.

Reactionaries and imperialists cannot be happy because socialism persists in Cuba. Socialism will persist in Cuba and continues to be linked to a right to happiness: “Men are transitory, the people remain; men are transitory, but ideas remain; men are transitory, but the sense of justice, of brotherhood, and equality among human beings, the right to defend their values, their hopes, their happiness remains” (200796). The metaphor of defense works with values and feelings, in this framework, the people is not defending their country, nation or territory, they are defending their right to happiness. It is the defense of moral, rather than material, goods what the rhetoric of happiness brings to the fore.

The special period is perceived as an economic, moral, sentimental and emotional blow that Cuba and the Revolution suffered while its enemies got happy and enjoyed seeking citizens who were against progress and fostered egoism and lack of solidarity. People is told to feel happy about all the things they can do, like in 60s, happy with the shared struggle. Polarities are draw between, against and for the government, being the government equal to the Revolution and the Revolution equal to progress, collectivism and solidarity. The U.S. Empire, on the other hand, is portrayed as happy with the tragedy.

Happiness is always set against inequality. When inequality becomes blatantly present in Cuban society, Castro “tries to meditate about what can the real world be and what can a happier man be”. Even then, he states he avoids mentioning any commodity and opts for the concept of inequality. It seems logic, happiness and inequality are a concept and its counter-concept.

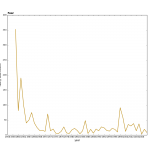

Envy

From 1959 until 1985 a template predominates in all premises containing the envy lexicon: “there is nothing we could envy in Cuba from the rest of the world”. Envy is proactively discouraged, “there is no envy to be felt, living in a communist country will be a great joy” (May 9, 1963). After 1964, the uses of envy bifurcate establishing two realms: one, utilized in the presentation of the self by Fidel Castro and/or the Party, that envies the present era in relation to the possibilities “we”—the party officials—in the past had; and a second one that applies the formula “x in Cuba has nothing to envy x in the world”. From the moment that communism is established in the political regime, envy becomes entangled with happiness in a convoluted way. What causes joy is the struggle, and therefore what is actually envied are the challenges, the obstacles, that allow the subject to carry on an exemplar role, “your noble struggle” (1972). What breaks the monotony of nothing to be envied but the noble struggle is a speech in 1985 in which Fidel Castro envies for first time a material thing: “We envy the European socialist countries, which are linked to the major deposits of oil and gas by gas lines and oil pipelines and high voltage electrical lines” (Youth and Student Dialogue on Latin American-Caribbean Foreign Debt, Sept 15, 1985).

Since the end of 1979, envy is also used to identify the enemy or, more generally, a subject whose values are antithetical to the Revolution. There is a lack of character linked to a lack of revolutionary values: “Our people are a clean-living, a pure people. Our party is a clean-living party, a pure party. No, they are not a people of opportunists or of schemers because intrigue and opportunism are not part of the proletarian spirit. Nor are envy or intrigue, or negligence, or irresponsibility. That is not proletarian. And when a worker is guilty of this it is simply because he does not share the spirit of his class. And they [our people] will struggle without haste, but tirelessly, against all the negative subjective factors which hinder, detain or block the revolution” (Santa Clara textile complex, Dec. 2, 1979)

In 1987, although the spirit of “The Cuban people have nothing to envy of other people (Jun 25, 1987) prevails, there is a turn, Fidel Castro admits that the capital has fallen behind in terms of health services and states the usual premise in prospective terms: “momentarily we will have health conditions that would have nothing to envy other capitals in the world”. Also, envy is hypothetically linked to the housing problem, a problem that was last mentioned together with envy in 1959 when the same dichotomy urban city versus rural areas was appealed to say that people in the city paying high rents ends up envying the farmers rustic houses for which they didn’t have to pay the high, i.e. abusive, prizes of the capital. Although up until 1982 the paradigm “nothing to envy” is mostly used to address rural areas –modified as “nothing to envy the city/the capital”, in 1987 again envy switches directions from the city to the conditions in rural areas. The dichotomy rural area/urban city, capital continues appearing regularly until 1989. Something that is overall new in the 80s is that there is a subject that envies, besides the presentation of the self that Fidel Castro draws in relation to the narrative of the new man.

In tune with an ideological framework highly informed by the modern idea of progress, the relationship with the past is mediated by envy. Given the interdiction imposed upon nostalgia, it appears that at times nostalgia is simply substituted for envy with the addendum of the heroic struggle. What is envied is the possibility of participating in an heroic present from a past era, or, the possibility that the youth has of participating in the heroic resistance of the present. All things considered, what is envied is the happiness of the struggle.

In the 90s, a very special turn occurs in the use of this lexicon. Between the 60s and 80s the vector “envy” went from the Cuban people to the outside world: “we [the Cuban people] have nothing to envy”. But then the vector changes directions in the 90s and we often see “the capitalists envy us for…” “the rest of the world envies us for…” (IV Congress FEU, 20 Dic. 1990). The capitalist envy the health system and the rest of the world Cuba’s valiant position and its educative system. Something never mentioned before 1991 in the list of “our X has nothing to envy outside world’s X” is democracy. In the crisis of 1993, Fidel Castro revisits the “history will absolve” dispositif he used in 1953 and1954, and adds some modifications: “History will judge us, not for what we had done before, but for what we do now in these circumstances. Nobody has to feel envy for 1968 or 1995, nor the Moncada, Sierra Maestra or Girón times” (National Assembly 15 Mar. 1993). It is clear that in place of envy here goes nostalgia or missing, or longing, but since the emotional regime didn’t encourage those bourgeois attitudes of looking towards the past instead of the future, he substitutes it by envy. At the terrible hecatomb that 1993 was, only him could miss the Moncada times. In 1994, he repeats this “envy” paradigm with the same premises: “we would love to be living in those guerrilla times that I remember with envy” (IV Encuentro Latinoamericano y del Caribe, 28 Jan, 1994). Most certainly the majority of the population remembered with envy most recent times, and if envying something it was the neighborhood whose relatives lived abroad and sent help. In 1996, one more crucial rhetorical change occurs. The possibility of envying material things –and a different purchasing power—is acknowledged: “Others have the privilege of having relatives abroad… What are we going to do? To die of envy? No, they then spend money and a part of it goes to the State coffers, it can help us to finish the Hospital” (Anniversary of the assault on the Moncada Barracks 26 Jul 1996).

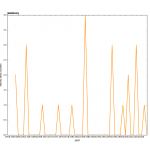

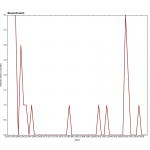

When aggregating by year the envy lexicons after 1959, one can see a series of peaks as the lexicon appears and disappears intermittently. The highest three peaks are in 1971, 1996 and 2001. In 1971 the template “nothing to envy” predominates together with a presentation of the self that swanks about youthfulness and lack of time. 1996 is a year when the discouragement and negation of envy reaches its most varied fields, going from envy to monetary help from abroad to other cities’ lack of envy towards Holguín for being the host for Moncada’s assault anniversary. When a subject is clearly defined as envying is either the enemy or Fidel envying the possibilities the revolution gave to the present youth. There is bad envy and good envy. Having introduced the possibility of bad envy –and envy to other socio-economic statuses—Fidel Castro then specifies being happy and not sad about “our” envy when in relation to youth and the future.

In 2001 the pattern of good and bad envy continues. On the one side the presentation of the self envies the possibilities, talents and heroic struggles of youth. As in 1987, Fidel Castro employs the envy in prospective terms, this time with an interesting and telling clarification of the category “past: “in a relatively brief period of time, the new would have absolutely nothing to envy the past, and I am referring to the past of our Revolution, not the past that preceded it” (15 Mar. 2001). Cuba is presented as the voice of just causes and as enjoying the enviable privilege of freedom of speech. On the other, the imperialists envy Cuba’s new form of democracy and the unity of the Cuban people. The connection with democracy first introduced in 1991, reappears in 2001.